I came across this copy of Paul de Ville's "The Eclipse Self-Instructor for Banjo" (1905) at a sheet music give-away. Sax players will recognize Paul de Ville (or deVille) as the author of the "Universal Method for Saxophone" (1908), a very good instruction book that is still in wide use today. I wondered for a moment if this could be the same person - but of course it is. How many Paul de Villes, writing music instruction books in 1905-1908, could there have been?

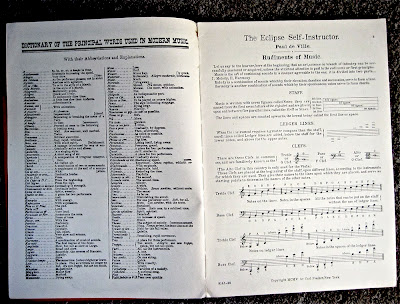

On the first page of the banjo book is a "Dictionary of the Principal Words Used in Modern Music." An identical list, under the title "A List of the Principal Words Used in Modern Music," appears on page 13 of the saxophone book. The next page of the banjo book starts a section called "Rudiments of Music." I thought that looked familiar as well. In fact, there is a "Rudiments of Music" section in the saxophone book too. The subjects, layout, and wording are similar but not identical, as though de Ville had revised his 1905 banjo version for the 1908 saxophone book.

But wait! My edition of H. Klosé's "Celebrated Method for the Clarinet" also has a similar "Rudiments of Music" section at the beginning of the book. And "A List of the Principal Words Used in Modern Music," the same list exactly, appears in Klosé, on page 120.

All three books were (or are) published by Carl Fischer. It looks as though it was company policy to include a standardized "Rudiments" section. Incidentally, on the Petrucci site I found a free download of an 1879 English language edition of the Klosé (pub. Jean White). Comparing it to my 1946 "Revised and Enlarged by Simeon Bellison" edition, it's possible to make some guesses as to which parts of the Klosé were simply lifted by Carl Fischer from the earlier Jean White edition (e.g., most of the wording in the translation from French to English), which parts may have been added in early Carl Fischer editions, (e.g., the "Rudiments" section) and which parts may have been added or rewritten by Simeon Bellison (substitution of less antiquated wording, much extra musical content).

So, back to the banjo book - after the 8-page Rudiments section, de Ville has 3 pages on how to play the instrument, followed by 8 pages of short exercises. Then he gets right down to business, with 139 "Standard, National, and Operatic Melodies." This would have been a pretty cool song collection for most Americans in 1905: Irish, civil war, minstrel show, Gilbert and Sullivan, Verdi, Stephen Foster, jigs, polkas. By comparison, the saxophone book is rather dry - no popular songs at all. I imagine that de Ville modelled the sax book after "serious" classical method books, like Klosé, or the Arban trumpet method.

According to an article on www.concertina.net, de Ville published "Eclipse Self-Instructor" books for accordion, concertina, banjo, flute, clarinet, guitar, mandolin, trombone, piano, saxophone, and violin, between 1893 and 1906. The concertina book is still in print (as are the later 1908 "Universal Method" and the Klosé clarinet method, of course).

De Ville seems to have taken his saxophone "Universal Method" seriously, more so anyway than the banjo book. It's aimed at students with patience and discipline, rather than at those just interested in playing popular songs. The "Eclipse" and "Universal" series were aimed at different sorts of customers.

It's interesting that de Ville, and the Carl Fischer company, thought that the saxophone was worthy of a method with a "serious" approach (and that it would sell). As to why that might be, I'm thinking about the social status of the saxophone in 1908. The popularity of the instrument at that time would have been based on its use in the very popular Patrick Gilmore (active 1848-1892) and John Philip Sousa (active 1880-1932) bands, and in thousands of town bands playing similar music at the time. The saxophone's ascendency in pop culture via vaudeville (e.g., the Six Brown Brothers, 1910s) and early commercial recordings (Rudy Wiedoeft, late 1910s and early 1920s) was still in the future. Jazz saxophone came even later.

De Ville is listed as having revised the Lazarus clarinet method c.1900 (Eastman library). In his Author's Note at the beginning of the "Universal Method for Saxophone," he calls the saxophone "my favorite instrument." Maybe he was a single-reed guy.

More about De Ville in my next post.