There's been some buzz lately around a video from YouTuber Adam Neely in which Adam discusses Jobim's "Girl From Ipanema" ("Garota de Ipanema"), including his explanation of Jobim's harmony on the bridge. Several musician friends have sent me the link, and there have been two threads on saxontheweb.com discussing the video (here and here). Last time I looked, this video had 1,226,782 views.

I've enjoyed other YouTube videos from Neely, but this one has some questionable information, IMHO. I'm going to take the bait and write up my comments. Here's his "Ipanema" video, if you haven't seen it yet:

The first issue that jumps out at me is the question of the proper key for "Ipanema." All of the published sheet music versions, and all of the fakebooks that I have seen, show the song in F. Adam tells us that this key is a "relic of American cultural hegemony, codified by decisions made at the Berklee College of Music in the 1970s." Strong words! He is referring to the Real Book (1974), which shows the tune in F.

Neely states that in Brazil, F is not regarded as the hip key for this song, and that for a Brazilian audience, you had better play it in Db, because "Db is thought of as the more authentic, Brazilian key." Why, you might ask? Because Db was the key used on the "Getz/Gilberto" album, the recording that made the song a worldwide hit in 1964.

I’m certain that Jobim always intended for this tune to be in F. There are several original Jobim manuscripts that you can view at jobim.org, all of them in F. Whenever Jobim performed it, it was in F, as nearly as I can tell from his live videos, except when he played it with Joao Gilberto. I played with Brazilian bands in the SF Bay Area for years, and the key for "Ipanema" was always F; no one ever suggested otherwise. My musician friends tell me the same thing. I have never heard that any other key is regarded as more authentic. But perhaps Neely has experience I don't have, or different sources of information.

The simple explanation for recordings in other keys is that those keys were chosen to accommodate the singer's best range. That's done all the time. I think it was in Db on the album because Joao Gilberto preferred that key. On some later recordings, Joao plays it in D.

Here is a 1962 live version with Jobim, Gilberto, and Vinicius de Moraes. They play it in F:

This reminds me of a story. Years ago, I was on a big-band gig for a corporate event. Eddy Arnold, the country singer, was at the event for some reason, and was scheduled to sing "September Song," accompanied by our pianist, Reed Struppa. Before the gig, when we were setting up, Eddy asked Reed to find the key where he would be most comfortable. They rehearsed a little, and came up with some little-used, awkward key. After the gig, Reed told me, "When they do that, I tell them OK, then when the time comes I just play it in the nearest easy key, C or F or whatever. They never notice the difference."

Anyway, back to Ipanema. Adam gives us some basic bossa nova history, and points out that the A section of Ipanema uses essentially the same harmony as the A section of "Take the A Train" (that is, I for 2 bars, V of V for 2, then II V I, with a bII tritone sub for the V in "Ipanema"). Here I agree with him. Incidentally, this harmony was not original with Billy Strayhorn, who wrote "A Train" in 1939. Strayhorn borrowed it from Jimmy McHugh's 1930 tune "Exactly Like You." Neely notes that this progression also appears in the A section of Jobim's "So Danco Samba." I'd add that Jobim's "Desafinado" follows this progression too, for the first 6 bars, before veering off into creative territory.

Here’s a video of Jobim playing “Ipanema” in Sao Paolo in 1994 at an “All Star Tribute.” It's a fairly good band: Jobim, Herbie Hancock, Joe Henderson, Ron Carter, Shirley Horn, Gal Costa, Jon Hendricks, Gonzalo Rubalcaba, Oscar Castro-Neves, Paolo Jobim, Harvey Mason, Alex Acuna. They play it in F. At 55:39 Jobim sings the "A Train" melody over the Ipanema A section, a sort of inside joke.

Neely points out some countermelody lines in the bridge (13:27 in his video) that Jobim clearly intended to be part of the song. Adam criticizes the Real Book compilers for not including these countermelodies. I agree that it would have made for a better chart, but let’s not be too judgmental; the Real Book was a great product for 1974. By the way, the current Hal Leonard legal version of the RB doesn't include the countermelodies either.

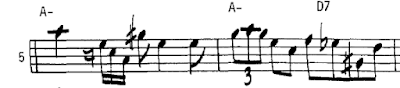

When Adam gets into explaining the harmony of the bridge to Ipanema, he gets into questionable territory, as I see it. Here is the bridge:

At first glance the chords do not seem to follow the "rules" of standard jazz harmony. But it makes sense to me this way:

The bass notes on the F#m7 (bridge bar 5-6) and D7 (bar 7-8) have an interesting effect and a certain logic. F# has continuity with the first tonality in the bridge. D7, besides being IVb7 in A, is V of the Gm7 that follows. These features do not interfere with the key centers Gb - A - Bb as described above.

As Neely remarks, there is a virtual "cottage industry" of YouTube videos and articles that try to explain the bridge. If you want to get into it, do a YouTube search for "Ipanema bridge analysis." Don't say I didn't warn you.

Neely's take on the bridge starts at 10:12 on his video. He hears the Gb as a IV in Db, B7 as a bVIIdom in Db, F#m7 as a II in E, D7 as a bVIIdom in E; Gm7 as a II in F, Eb7 as a bVIIdom in F.

It's an interesting take. With some effort, I can hear it as he describes. I can't say he is exactly "wrong," but his explanation doesn't really work for me.

I don't want to get too deep in the weeds here, but:

Neely goes on to say that he hears the countermelody as a blues lick. I don't. It's true that you can shoehorn the notes of the countermelody lick into a blues scale that would seem to fit Neely's conception of the key centers, but I just don't hear it.

Of course, reasonable people can disagree.

Here's yet another take on the bridge, more scales-based, from my friend Larry Lewicki:

Any of these analyses - Neely's, mine, Larry's, and the various YouTubers' - can serve as the conceptual basis for a perfectly good solo, depending on how the player's melodic sense operates. In that respect, they are all just fine. However, if I'm trying to figure out what Jobim may have been thinking, I kind of like my approach.

Adam states that the harmonic ambiguity he perceives in "Ipanema" is typical of bossa nova. I think that as a generalization, that's somewhat of an overstatement. Mostly, the classic bossas can be explained fairly neatly in standard jazz terms.

Jobim was a particularly creative composer, a generation younger than the "Great American Songbook" composers, building on their work. And even in Jobim's songs, especially in the earlier ones that made him famous, most of the harmony is pretty straightforward.

Quite a few Great American Songbook standards had an introductory section called a "verse." At 30:28 in his video, Adam points out the introductory verse in the live 1962 Jobim/Gilberto/Vinicius recording. I hadn't known about that. Desafinado has a verse too, that Jobim used in performance. He even had English lyrics for it. But the "Ipanema" verse was news to me. Thanks to Adam for pointing it out!

It does seem that this verse was not exactly intended to be part of the composition, though, but rather was created for a particular occasion.

I asked my friend Guto for a translation, and here it is, with his comments:

Guto also noticed some musical jokes in the verse:

Besides the 1962 live recording, the only other place I've heard this verse is in this great video with Jobim and Gilberto, I think from 1992. Joao sings the verse himself, and they play the tune in D:

Beginning at 23:12 in his video, Adam discusses a 1962 version by singer Pery Ribeiro that may predate even the 1962 Jobim/Gilberto/Vinicius recording. Because it is probably the earliest recorded version of the song that we have, Neely finds importance in 1) the key it's played in, and 2) the harmony used for the bridge.

This version is in G, leading him to say that "The original is in the key of G." But there's no evidence that Ribeiro's was the "original" version. This is an unwarranted assumption. More likely, the key was chosen to accommodate Ribeiro's voice.

About the harmony in Ribeiro's version - Neely presents this arrangement as a sort of "missing link" between a hypothetical Tin Pan Alley harmonization and the "bossa nova" final version. But it's quite likely that the harmony used in this recording was the work of Ribeiro's arranger; it was not necessarily an early Jobim version of the song.

Neely seems to be saying that the "final" version of the bridge harmony was actually the work of Joao Gilberto, editing and simplifying Jobim's "original" harmony as used in the Ribeiro recording. But there are two unwarranted assumptions here: 1) that the Ribeiro harmony was Jobim's, and 2) that it was Gilberto who created the "final" version.

I really did enjoy Neely’s video, in spite of a few disagreements. Hopefully some of those million-plus views will get some younger musicians interested in Jobim and bossa.

To close, if you'll forgive me, here is an old musician's joke, that an old musician told me during a band break:

I've enjoyed other YouTube videos from Neely, but this one has some questionable information, IMHO. I'm going to take the bait and write up my comments. Here's his "Ipanema" video, if you haven't seen it yet:

What is the proper key for this song?

Neely states that in Brazil, F is not regarded as the hip key for this song, and that for a Brazilian audience, you had better play it in Db, because "Db is thought of as the more authentic, Brazilian key." Why, you might ask? Because Db was the key used on the "Getz/Gilberto" album, the recording that made the song a worldwide hit in 1964.

I’m certain that Jobim always intended for this tune to be in F. There are several original Jobim manuscripts that you can view at jobim.org, all of them in F. Whenever Jobim performed it, it was in F, as nearly as I can tell from his live videos, except when he played it with Joao Gilberto. I played with Brazilian bands in the SF Bay Area for years, and the key for "Ipanema" was always F; no one ever suggested otherwise. My musician friends tell me the same thing. I have never heard that any other key is regarded as more authentic. But perhaps Neely has experience I don't have, or different sources of information.

The simple explanation for recordings in other keys is that those keys were chosen to accommodate the singer's best range. That's done all the time. I think it was in Db on the album because Joao Gilberto preferred that key. On some later recordings, Joao plays it in D.

Here is a 1962 live version with Jobim, Gilberto, and Vinicius de Moraes. They play it in F:

This reminds me of a story. Years ago, I was on a big-band gig for a corporate event. Eddy Arnold, the country singer, was at the event for some reason, and was scheduled to sing "September Song," accompanied by our pianist, Reed Struppa. Before the gig, when we were setting up, Eddy asked Reed to find the key where he would be most comfortable. They rehearsed a little, and came up with some little-used, awkward key. After the gig, Reed told me, "When they do that, I tell them OK, then when the time comes I just play it in the nearest easy key, C or F or whatever. They never notice the difference."

Harmony of the A section

Anyway, back to Ipanema. Adam gives us some basic bossa nova history, and points out that the A section of Ipanema uses essentially the same harmony as the A section of "Take the A Train" (that is, I for 2 bars, V of V for 2, then II V I, with a bII tritone sub for the V in "Ipanema"). Here I agree with him. Incidentally, this harmony was not original with Billy Strayhorn, who wrote "A Train" in 1939. Strayhorn borrowed it from Jimmy McHugh's 1930 tune "Exactly Like You." Neely notes that this progression also appears in the A section of Jobim's "So Danco Samba." I'd add that Jobim's "Desafinado" follows this progression too, for the first 6 bars, before veering off into creative territory.

Here’s a video of Jobim playing “Ipanema” in Sao Paolo in 1994 at an “All Star Tribute.” It's a fairly good band: Jobim, Herbie Hancock, Joe Henderson, Ron Carter, Shirley Horn, Gal Costa, Jon Hendricks, Gonzalo Rubalcaba, Oscar Castro-Neves, Paolo Jobim, Harvey Mason, Alex Acuna. They play it in F. At 55:39 Jobim sings the "A Train" melody over the Ipanema A section, a sort of inside joke.

The bridge

Neely points out some countermelody lines in the bridge (13:27 in his video) that Jobim clearly intended to be part of the song. Adam criticizes the Real Book compilers for not including these countermelodies. I agree that it would have made for a better chart, but let’s not be too judgmental; the Real Book was a great product for 1974. By the way, the current Hal Leonard legal version of the RB doesn't include the countermelodies either.

When Adam gets into explaining the harmony of the bridge to Ipanema, he gets into questionable territory, as I see it. Here is the bridge:

Gbmaj7: New key, up a half step from the A section (think of it as F#maj7).

B7: IVb7 in F#, a blues-type IV chord. Introduces the blue note A natural, the b3 in F#.

F#m7: It's really A6 with F# in the bass, the I of a new key.

D7: IVb7 in A, blues IV chord again. Introduces blue note C natural, b3 in A.

Gm7: It's really Bb6 with G in the bass, the I of a new key.

Eb7: Again, it's IVb7, a blues IV chord. Introduces the note Db, b3 in Bb.

The last 4 bars are a turnaround back into F, to set up the last A section.

The bass notes on the F#m7 (bridge bar 5-6) and D7 (bar 7-8) have an interesting effect and a certain logic. F# has continuity with the first tonality in the bridge. D7, besides being IVb7 in A, is V of the Gm7 that follows. These features do not interfere with the key centers Gb - A - Bb as described above.

As Neely remarks, there is a virtual "cottage industry" of YouTube videos and articles that try to explain the bridge. If you want to get into it, do a YouTube search for "Ipanema bridge analysis." Don't say I didn't warn you.

Neely's take on the bridge starts at 10:12 on his video. He hears the Gb as a IV in Db, B7 as a bVIIdom in Db, F#m7 as a II in E, D7 as a bVIIdom in E; Gm7 as a II in F, Eb7 as a bVIIdom in F.

It's an interesting take. With some effort, I can hear it as he describes. I can't say he is exactly "wrong," but his explanation doesn't really work for me.

I don't want to get too deep in the weeds here, but:

1) I don't hear the bridge as starting in the key of Db (that would make Gbmaj7 the IV, with a Lydian tonality). I hear it in Gb, starting on the I. Jobim very often used major 7th melody notes over tonic major 7 chords, as he does in the A section of this song, and that's what we have here.

2) I'm not the only one who hears it that way; some other YouTubers in this "cottage industry" agree with me, as do some of the commenters in the saxontheweb threads on this subject.

3) Occam's Razor favors my explanation.

Neely goes on to say that he hears the countermelody as a blues lick. I don't. It's true that you can shoehorn the notes of the countermelody lick into a blues scale that would seem to fit Neely's conception of the key centers, but I just don't hear it.

Of course, reasonable people can disagree.

Here's yet another take on the bridge, more scales-based, from my friend Larry Lewicki:

FWIW, I don’t analyze the bridge the same way as Peter. I just see scales with shared pitches. I almost picture Jobim doing his scales F# major, F# melodic minor, F# dorian ... just changing one pitch.

F#Δ - F# major

B7#11 - F# melodic minor (an essential element of blues - the IV7) (shares 6 notes with F# major)

F#-7 - F# dorian (shares 6 notes with F# melodic minor)

D7#11 - A melodic minor - shares 5 notes with F# dorian (check Tenderly bars 5-6, 21-22)—- D7 is the dominant of G minor

G-7 - G dorian

Eb7#11 - Ab melodic minor - shares 5 notes with G dorian (Tenderly cadence)—- tritone sub of Eb7 is A7 - Am7 is very close - that’s the beginning of the final 2 bars - Bebop iii VI7 ii V7 cadence in F.

I don’t see the F#-7 as a inversion for an AΔ.... because of the dorian mode D#

Any of these analyses - Neely's, mine, Larry's, and the various YouTubers' - can serve as the conceptual basis for a perfectly good solo, depending on how the player's melodic sense operates. In that respect, they are all just fine. However, if I'm trying to figure out what Jobim may have been thinking, I kind of like my approach.

Harmonic ambiguity as a defining feature of bossa nova

Jobim was a particularly creative composer, a generation younger than the "Great American Songbook" composers, building on their work. And even in Jobim's songs, especially in the earlier ones that made him famous, most of the harmony is pretty straightforward.

Does "Ipanema" have an introductory verse?

Quite a few Great American Songbook standards had an introductory section called a "verse." At 30:28 in his video, Adam points out the introductory verse in the live 1962 Jobim/Gilberto/Vinicius recording. I hadn't known about that. Desafinado has a verse too, that Jobim used in performance. He even had English lyrics for it. But the "Ipanema" verse was news to me. Thanks to Adam for pointing it out!

It does seem that this verse was not exactly intended to be part of the composition, though, but rather was created for a particular occasion.

I asked my friend Guto for a translation, and here it is, with his comments:

That intro is indeed very interesting. It seems it was a one off for that album, almost like an insider joke the trio Tom, Joao, Vinicius was telling to the live audience before the song starts. They go:

João: Tom, e se você fizesse agora uma canção?

Tom, how about you now make a song?

Que possa nos dizer, contar o que é o amor

One that says, tells us what love is

Tom: Olha Joãozinho, eu nao saberia

Look dear João (or little Joao, in an affective way), I wouldn’t know how

Sem Vinícius pra fazer a poesia

Without Vinicius to make the poetry

Vinícius: Para essa canção se realizar

For this song to come together

Quem dera o João para cantar

I wish João would sing

João: A, mas quem sou eu, eu sou mais vocês

Oh, but who am I, I’m more you both (in the sense of I trust you’d do a better job)

Melhor se nós cantássemos os três

We’d better sing the three of us

Guto also noticed some musical jokes in the verse:

... the second line Tom sings, “sem Vinicius pra fazer a poesia,” sounds the same as this section from Desafinado:

and the last phrase from Joao, “melhor se nos cantassemos os tres,” sounds like the ending phrase of One Note Samba.

Besides the 1962 live recording, the only other place I've heard this verse is in this great video with Jobim and Gilberto, I think from 1992. Joao sings the verse himself, and they play the tune in D:

Pery Ribeiro’s 1962 version

Beginning at 23:12 in his video, Adam discusses a 1962 version by singer Pery Ribeiro that may predate even the 1962 Jobim/Gilberto/Vinicius recording. Because it is probably the earliest recorded version of the song that we have, Neely finds importance in 1) the key it's played in, and 2) the harmony used for the bridge.

This version is in G, leading him to say that "The original is in the key of G." But there's no evidence that Ribeiro's was the "original" version. This is an unwarranted assumption. More likely, the key was chosen to accommodate Ribeiro's voice.

About the harmony in Ribeiro's version - Neely presents this arrangement as a sort of "missing link" between a hypothetical Tin Pan Alley harmonization and the "bossa nova" final version. But it's quite likely that the harmony used in this recording was the work of Ribeiro's arranger; it was not necessarily an early Jobim version of the song.

Neely seems to be saying that the "final" version of the bridge harmony was actually the work of Joao Gilberto, editing and simplifying Jobim's "original" harmony as used in the Ribeiro recording. But there are two unwarranted assumptions here: 1) that the Ribeiro harmony was Jobim's, and 2) that it was Gilberto who created the "final" version.

I really did enjoy Neely’s video, in spite of a few disagreements. Hopefully some of those million-plus views will get some younger musicians interested in Jobim and bossa.

To close, if you'll forgive me, here is an old musician's joke, that an old musician told me during a band break:

A jazz group has a gig at a bar in Chicago. The bass player lives across the border in Indiana. He has a history of showing up late for gigs. When it's time for the downbeat at 9:00, the bass player still hasn't shown up. At the first break at 9:45, still no bass player. The band leader is getting increasingly angry. Finally, at 10:30 the bartender goes up to the band leader and says, "Your bass player is on the phone. He's stuck on the bridge to Indiana."

The bandleader says, "Man...there is no bridge to Indiana."